08/06/2008

Everything is art

Theatre has existed since the beginning of the world. Everything is a form of art: even life itself. For me, theatre is a museum of the abstract in which lots of things happen at the same time. Theatre is a place where we can meet with everything. Theatre is a great place to describe history and to talk about the future. It is a metaphysical zone of freedom – saying Simon Mol.

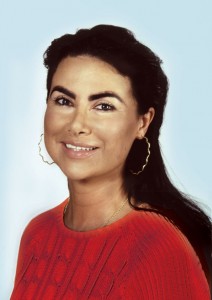

SIMON MOL

Cameroonian journalist, writer, director and actor

talks to Damian A. Zaczek

You live in Warsaw, edit a newspaper, write theatre plays and appear in them. How is it that you have all these interests?

My interests in literature and art developed at home. My father is a raconteur, he tells stories. Children and older people come to him to hear his tales, adventures and stories about the world. My father composes music and sings. I have inherited my artistic talents from him.

Where are you from?

From the historic town of Buea, which was the capital of Cameroon when my country was a German colony. Stanisław Rogoziński, the Polish researcher and anthropologist, lived in Buea. He spent 25 years amongst Cameroonians. He probably very much liked timba-na`mbusa, a dish of the Bakweri people. He knew the Bakweri language very well – it is my mother tongue alongside English. Bakweri historians stress that it is not possible to talk about Buea’s history without referring to Rogoziński.

What did you do in Buea?

I played football since childhood, reaching the professional first division teams: Top Tarzan Mutengene and Tico United. The latter advanced from the 2nd to the 1st division, but was then relegated. But as regards my profession, I am a journalist.

Which newspapers did you work for?

For the political weekly called “The Sketch” and later for “Cameroon Life Magazine”, another paper covering politics. It circulated in the English speaking part of Cameroon. I’ll explain, Cameroon is divided into 10 counties: in eight of them French is spoken and English in two. It is the result of two successive colonisations: the French and the British.

Why did you have to leave Cameroon?

For the last 24 years Cameroon has been ruled as a dictatorship by president Paul Biya. I wrote articles about government corruption and about ministers who defrauded money. I was arrested for that and spent several weeks in prison. After my release, I was banned from working as a journalist. However, I continued to write for various papers. Then at a certain point it became dangerous and I had to flee. First to Equatorial Guinea, then on to Gabon. The Gabon authorities have very good relations with the government of Cameroon, so it was not safe their either. I fled to Nigeria, and from there I went to Ghana. I spent one and a half years in Ghana working on a very radical paper the “Weekly Inside”. We were very critical of the Ghanaian president, Jerry Rawlings. The editor in chief of the Weekly Inside was arrested 30 times. Such a radical newspaper could not attract advertising, because everyone was afraid of buying space in something so critical of the government. So, there was not enough money to pay the employees regularly. To survive, I had to start working for the government newspaper “The Democrat”, but at the same time I was also publishing texts in the opposition’s Weekly Inside. After a while, the editor in chief of The Democrat began to dislike this. He demanded that I make a choice. I chose to remain with the opposition paper. Such were my views and moral values. The Cameroonian government protested to the government of Ghana about my articles. I was locked in prison for six weeks. Cameroon’s secret police started to be interested in me. It became dangerous and once again I had to escape.

How did you end up in Poland?

As a writer and a poet, I belong to the PEN Club. I found out in Ghana that the International Congress of the PEN Club was to take place in Poland in 1999. Managed to get an invitation and I came over. I immediately asked for political asylum.

How long did you have to wait?

One and a half years. I lived during that time at the centre for refugees in Dębak.

You set up a theatre in Warsaw?

Yes. The “Migrator Theatre” is registered as an international theatre foundation for immigrants. We have 20 actors from 12 countries in the company and also a few Poles. We often receive guest appearances from professional actors from such Warsaw theatres as the Narodowy and the Rozmaitości. We perform in Polish and in English. We have amateur as well as professional actors. Mikołaj Klimek from the Narodowy acts with us, as well as Kasia Regulska, Christian Emany from the Congo, who appears at the Rozmaitości Theatre, and also Szymon Malinowski, Adam Rogoziński and others.

Do you have a regular stage?

We do not have our own theatre, but we are looking for one. Some of the institutions which cooperate with us, such as The National Museum of Ethnography, and the Austrian Forum of Culture, lend us their halls. But we play wherever we are invited: in cultural centres, such as in Bielany, and we hold our rehearsals in high schools, such as the one on Raszyńska street.

Why did you think up a theatre here in Warsaw?

Theatre has existed since the beginning of the world. Everything is a form of art: even life itself. For me, theatre is a museum of the abstract in which lots of things happen at the same time. Theatre is a place where we can meet with everything. Theatre is a great place to describe history and to talk about the future. It is a metaphysical zone of freedom.

How many plays has the Migrator Theatre performed?

Four plays during three years of existence. I should add that the theatre was only registered as a foundation at the beginning of this year. My play “Journeys to a new homeland” was performed last year in English at the international human rights conference at the Victoria hotel. We put on the musical “A Frozen Moment” at the Museum of Ethnography, in the Cultural Centre in Bielany, at the Higher School of Social Psychology and also at the Victoria hotel. We are working on a new play called “21st Century Man”, which we plan to premiere in October. European Voluntary Service is helping to bring over for 9 months a professional actress from Georgia, with whom we will also do various projects.

Why did you decide to start publishing the Polish-English bimonthly “Voice of Exile”?

I initially worked with The Warsaw Voice. But I came to the conclusion that refugees in Poland are missing their own paper. I wanted to write about issues important to us, provide information about Poland and to make Poles more aware of the refugees’ cultures and societies. I wanted to create a publication which would focus on issues of emigration, on the problems of assimilation and on human rights. We want to demonstrate various points of view, so we also have Poles writing for our paper. They are mainly students. We also have collaborators abroad. I would like to carry out an international study of the problems faced by refugees in various European countries. I would publish the findings from this exercise in Polish. It will be a compendium of knowledge for Polish staff involved with refugees. They will be able to compare approaches used in other countries with those in Poland, and get to know other’s experiences. There is no information about this in Polish, which is why I want to do this.

What is the Voice of Exile’s print run?

Initially, we produced a thousand copies, but now we have five thousand. But that is not enough. We give it out for free. We would like it to be sold in the Empik shops but we do not have the funds to ensure the publication’s continuity.

Do the Polish government’s agencies help you?

No. We once received a donation from the FIO – the Forum for Civil Initiatives and one from the Social Policy Office of the Warsaw city authority. We are looking for funds the whole time.

You are the secretary general of the Association of Refugees in Poland. Are the refugees in Warsaw well enough organised to do something together?

The refugee community needs a good leader and good, sensible initiatives. The community will then be able to start functioning. The association is open to all refugees from all countries.

What does the association do?

Like others, it has serious financial difficulties. But we help refugees as much as we can. We work together with solicitors offices, we help in completing asylum application forms, we give advice on living in Poland, and we have opened the doors to many of the institutions which help refugees. The city has provided us with an office, but we don’t have enough money to pay the rent.

What do refugees complain about in Poland?

Above all, about the lack of accommodation. As political refugees we have the same rights as Poles. So, we should be entitled to council flats. Earlier the city assigned us only five apartments, but this year not a single one. Refugees also have a right to work but it is actually very difficult to find employment. If the Voice of Exile had enough funds, it could employ several people.

What do you particularly miss in Poland?

I am in a very difficult financial situation. You can see how I live. I do not even have a bathroom. I am 33 and I would like to start a family, but how can I do this in such a situation? Apart from that I don’t lack anything. Nowhere is living easy, not even in my country. I just have to adjust to the current situation.

Don’t you want to travel further around the world?

No, I do receive quite a few invitations to travel around the world, but I like coming back to Poland. It is now my home. The European Union no longer has borders. There is no sense in moving from Warsaw.

What do refugees expect from Polish people?

Not very much. Mainly acceptance of people from a separate culture, with different customs and a distinct skin colour. There is racism in Poland, although Poles are generally friendly and open. I have experienced racist behaviour on my own skin – I have been beaten up twice.

Who are the racists?

They are ignorant people, some have mental problems. However, they are being cleverly manipulated by leaders who are the real racists. They are not the usual people you meet in the street. I believe that racism is organised by politicians.

Whom do you have in mind?

I don’t know: I have not looked into the history of fascism, which is everywhere – not only in Poland but in the whole of Europe and in Africa, for example: the tribal butchery of the Tutsis and the Hutus. I think that politics is like religion: people believe blindly in their politicians. Thank God that most people are not racist. But the minority has many opportunities to manipulate young people. This is the biggest problem.

Are worried of walking the streets?

No, it is not that bad in Warsaw.

What are your dreams?

I would like to be able to work in peace, writing articles, plays and books. Influenced by Mickiewicz’s “Dziady”, I wrote a book about the Festivals of the Dead in Poland and Africa. I discovered many common customs between the Polish and African religions. I want to concentrate on showing the common values in Polish and African culture and traditions. I would like to demonstrate that despite the differences in skin colour, we are still the same, we live in one world and we are only separated by geography.

Thank you for talking.

MY PERSPECTIVE

Demolition time

The Kaczyński brothers have announced the creation of the 4th Republic. However, it looks like they are currently at the stage of completely dismantling and destroying the structures set up after the fall of communism. więcej...